What is Permaculture

By core team member, Ambra Pirker

“Permaculture (permanent culture) is the conscious design and maintenance of agriculturally productive ecosystems which have diversity, stability, and resilience of natural ecosystems. It is the harmonious integrations of landscape and people providing their food, energy, shelter and other material and non-material needs in a sustainable way. Without permanent agriculture there is no possibility of a stable social order.” - Bill Mollison

History

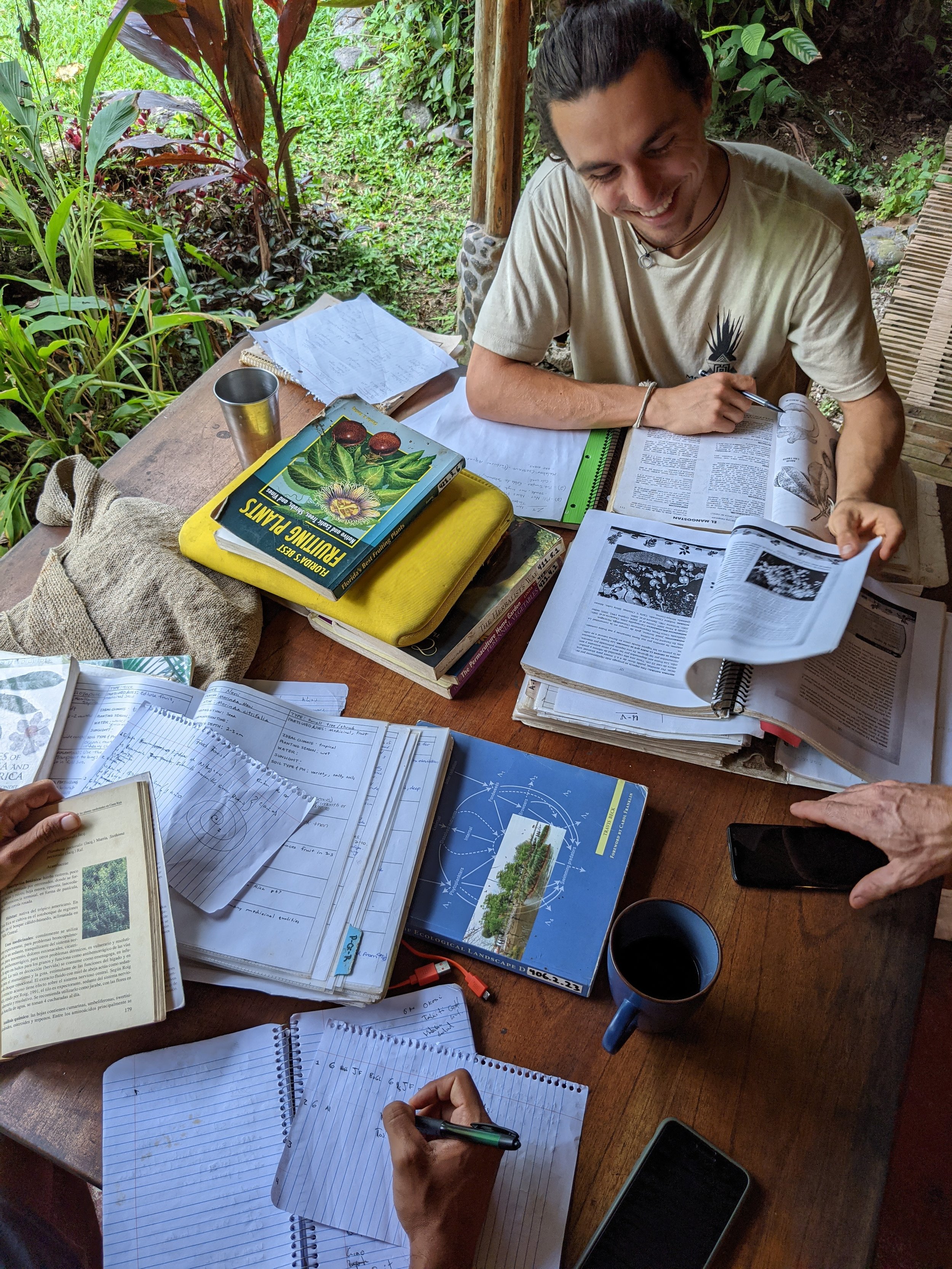

Permaculture as a concept was coined in the late 1970s, between 1972 and 1974 Bill Mollison worked on developing an interdisciplinary earth science with help from David Holmgren in the later years. In 1981 the concept had matured sufficiently and it was thought of as an applied design system to the first 26 students through a 140-hour lecture series. The first literature around permaculture were two foundational texts: Permaculture One (1978), Permaculture Two (1979) followed by PEMACULTURE A Designers’ Manual (1979), the latter is considered the Permaculture ‘bible’ by many. In 2002 David Holmgren released the book “Permaculture- Principals & Pathways beyond Sustainability” where he summarized the principals into 12 and offered a smaller, easier but thorough read. Nowadays there are many different books around permaculture, many of them leaning to specific topics that fall under the big permaculture umbrella; some are more on the social side, many focus on homesteading and gardening and some are centered around agroforestry and tree crops.

Evolution

Permaculture’s concept has evolved since the 1970’s, in its beginning the focus was around the design of ecological, regenerative and smart agriculture with the idea of creating a permanent agriculture; with an emphasis on perennials, tree crops, water conservation, earthworks, soil improvement, biodiversity and much more. Many of the proposed systems and methods were drawn out or inspired by indigenous knowledge around land use and care. Mollison independently researched and published a three-volume treatise on the history and genealogies of the descendants of the Tasmanian aborigines, this interest and dedication around indigenous culture was key in the developing of permacultures basis.

Nowadays permaculture has a huge social side with the inspiration of creating a permanent culture of sustainable, regenerative, cooperative and compassionate living; while giving the power back to the people to design their lives in accordance to their values. Permaculture is helping in the creation of a network, a web of interconnected visions, dreams, projects, ideas and people, with a common intention of doing good for each other and the planet.

“Great change is taking place. These are not as a result of any one group or teachings, but as a result of millions of people defining one or more ways in which they can conserve energy, aid local self-reliance, or provide for themselves.” - Bill Mollison

Definitions

Permaculture is a macro-concept that involves many different topics, methods, systems and ideas. Ideas like moving back to the land, using nature as our guide, applying ecology in our productive systems, reconnecting with the cycles of nature, approaching life holistically, creating stable local economies, regenerating the landscape and our relationships with others, investing in resiliency and interconnectivity; are in the heart of permaculture. Since the beginning of permaculture, the sense of shared work has been central, “we could say that there are as many permaculture definitions as there are permaculturalists.” (People and Permaculture, 2012)

I personally like to describe permaculture as: “An ethically based design system for human habitation and regenerative living that encompasses most aspects of life as a part of this planet; based on observation, inspired by pattern, inclusive, biodiverse, holistic and kind.”

Essentially permaculture is a design methodology that has foundational ethics and core principals, that can be applied to most aspects in life. When practicing permaculture, the ethics are the guides and the principals are the canons, so for example when designing a new system or element first we evaluate if it respects the four ethics. There is a lot to say about each of these ethics, the following is a brief summary; to learn more check out our blog article The Ethics of Permaculture.

Ethics

1) The first ethic is Earth care, when considering that planet earth is our sole and only home the need to move away from our extractive, materialistic, consumption-based society becomes obvious. Taking care of nature’s resources needs to be a central part of any human endeavor, protecting our flora and its genetic diversity should be in mind every time we sew a seed. Defending our fauna and understanding their importance in ecological balance should be part of every anthropocentric project. Protecting and improving our soil, respecting our waters and using them rationally, understanding the importance of clean air and minimizing our contributions to its contamination, all of this is just the start.

2) The second ethic is People care, meeting tangible and intangible needs of humans is central in permaculture, we are not just talking about human rights, we are going way further into providing the space for people to flourish. Right livelihood is a common term in permaculture, based on the idea of working on something that feels right individually, suits our needs, and is in line with our ethics. When we think of people care, we think about the wellbeing, happiness, health and support that people need, not just in our immediate proximity like our family and friends, but also in our community and for the humans of the world, what can we do today to improve the life of others? Permaculture helps us remember how important it is to shift our attention onto how we interact with each other. We have the chance to support people doing good for the planet, for others and themselves, creating local economies and supporting ethically based business’ will have huge positive repercussions in our destiny as humans.

3) The third ethic is Fair share, also know as “set limits to consumption” or “redistribute surplus.” We need to live within the carrying capacities of the planet, in a finite world we can’t follow an infinite thirst for materialistic goods. Redistribution of resources including money, food, knowledge, skills, education, land, and time are needed if we want a prosperous future. This may sound utopic, but the reality is that there are enough resources on the planet to allow every human to have a balanced and enjoyable life, but the culture of consumerism and accumulation has enabled some to have way more than what they need. Permaculture promotes a simpler life, where we are able to appreciate what is actually important and necessary for humans to thrive. Luxury and opulence have no place in permaculture. Fair share is personal responsibility and we should take it seriously.

4) The fourth ethic is Transition, this one wasn’t part of the literature for a long time, it came as a compromise around time and cultural context. In this ethic the general idea is that change takes time, when switching to a different paradigm; capital is a limiting factor since in our current world a greener life is usually more expensive than a mainstream one, and honestly there is no valid reason to prolongate that reality. If big industries were truly paying the honest price of oil and big ag wasn’t subsidized by the state, the greener alternative would cease to be more expensive. Transition ethic also helps us come to terms with the time needed for change, the system that inhabits our society has been around for a long interval, a new age is coming as our only option for the prosperity of our species. I believe that permaculture is a great starting point in the creation of our next society.

There is a lot more to add to all of the ethics of permaculture, an important point to mention is that they are open for interpretation, so the extent and detail that every permaculture project is applying them to their decision-making will vary. There is no permaculture body that supervises if a so-called permaculture farm is actually taking good care of their employees or helping the surrounding community. This may be seen as a flaw in the construct of permaculture, but it’s a genuine effort for decentralized, independent, self-reliant change. The evaluator of genuine permaculture should be the education of the multitude, we have the authority to exclaim when the ethics are not being respected, caring for permaculture is supporting it.

Principles

Permaculture also has several principles that guide decision making, they vary from author to author, but focus on similar ideas. Bill listed five principals in the book PEMACULTURE A Designers’ Manual (1979):

Work with nature rather than against it: assisting rather than impeding nature, understanding natural succession and using it in our favor.

The problem is the solution: everything can be a positive resource, figuring out how we may use it as such depends on us.

Make the least change for the greatest possible effect: change is a constant in nature but when it comes from our development it’s many times very damaging. Designing to minimize change and maximize positive effect is central for a regenerative future.

The yield of a system is theoretically unlimited: the imagination and information are the only limits to the number of uses of a resource within a system.

Everything gardens: every creature makes its own garden and has an effect on its environment.

David Holmgren proposes 12 principals in the book Permaculture- Principals & Pathways Beyond Sustainability (2002), take in consideration that the first 6 principles study systems from the bottom-up perspective and the second 6 principals emphasize the top-down organization and relationships that tend to develop in co-evolution. The following is just a brief mention of the principals, to learn more check out the blog “Applied Permaculture Principles.”

Observe and interact: observation should be the teacher of any action, interacting the lessons. “Careful observation and thoughtful interaction.”

Catch and store energy: understanding energy in a broad sense, there are many different types of energy, some are solar, wind, biomass, soil, rain, heat, commitment, passion and love. “Make hay while the sun shines.”

Obtain a yield: yields of many types; harvests, fauna, habitat, knowledge, beauty etc., design systems to provide self-reliance at all levels.

Apply self-regulation and accept feedback: identifying positive and negative feedback loops. There is self-regulation in a system with a positive feedback loop. Accepting feedback will allow us to improve our designs to the point of self-reliance.

Use and value renewable: renewable resources are all which can be renewed and replace by natural processes over reasonable periods of time, and renewable services are the ones received by plants, animals, soil and water without damaging or consuming them.

Produce no waste: minimize pollution and waste by using all outputs, there is no waste in nature. Closing cycles with organic transformation of biomass and waste minimalist (refuse, reduce, reuse, repair and recycle.)

Design from patterns to details: the closer we get the harder it is to understand the bigger picture, pattern recognition is central. Patterns in nature are the arrangement of parts into a whole, our main source of inspiration and the answers of innumerable questions. Self-organization from symbiotic coevolution of nature.

Integrate rather than segregate: the integration of parts, elements, and humans is as important as themselves. Developing positive and reciprocal relationships lead to resiliency, balance, productivity, stability and effectiveness. Each element performs many functions and each important function is supported by many elements. Designing for synergistic relationships as a central point.

Use small and slow solutions: “Systems should be designed to perform functions at the smallest scale that is practical and energy-efficient for that function.” Start slow, receive feedback and expand accordingly.

Use and value diversity: diversity is key for balance. Diversity of ideas, knowledge, experience, age, culture, language, food and so on, are our tools for adapting to change and thriving in an uncertain future. Diversity in agriculture allows for resiliency and security.

Use edge and value the marginal: greater diversity of life in the region where the edges of two adjacent ecosystems overlap. There are special conditions in the transitions zone of two different areas, that allow for unique species or interactions.

Creatively use and respond to change: “The designer’s imagination and skill usually limit productivity and diversity before any physical limits are reached.”

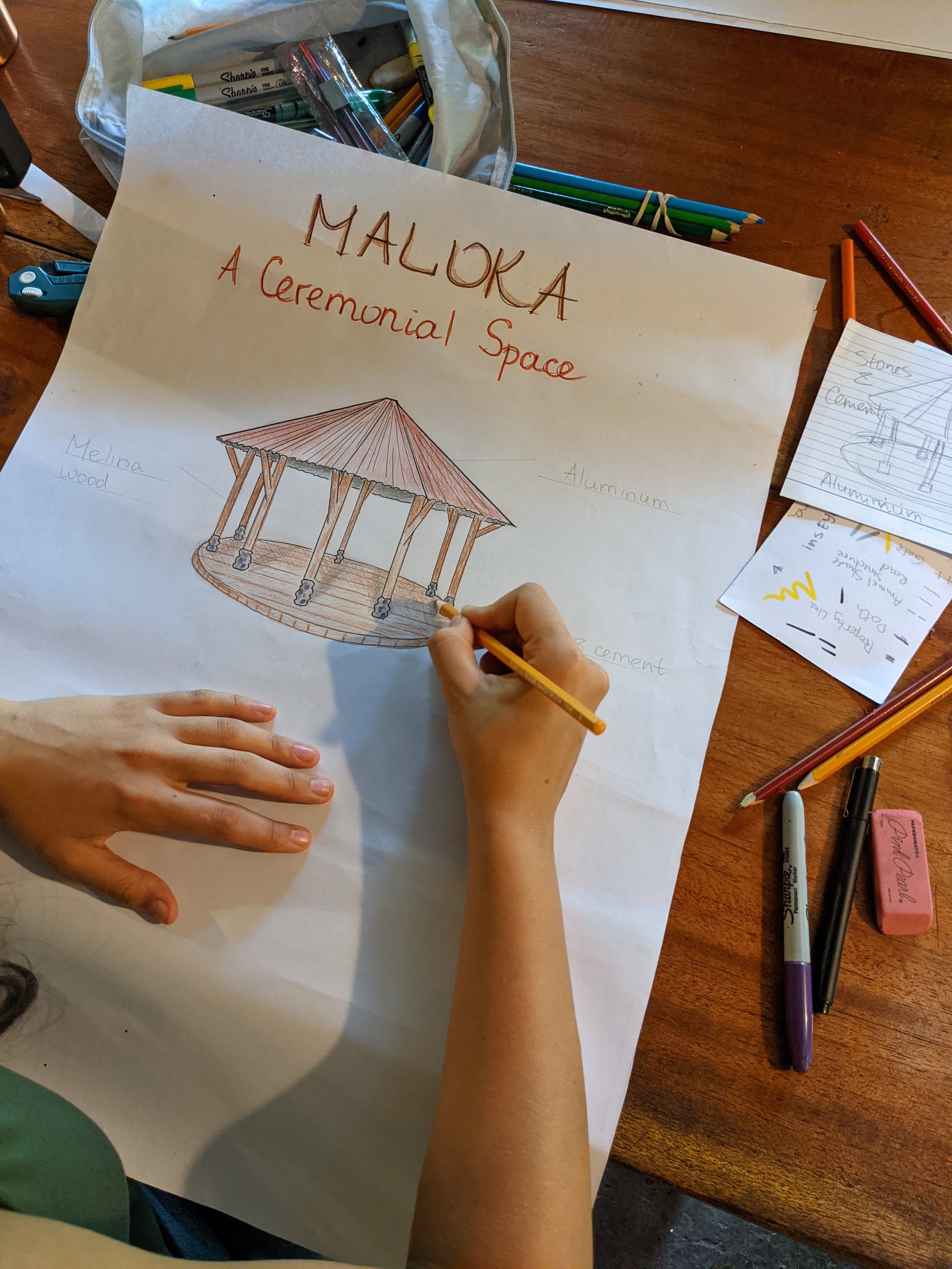

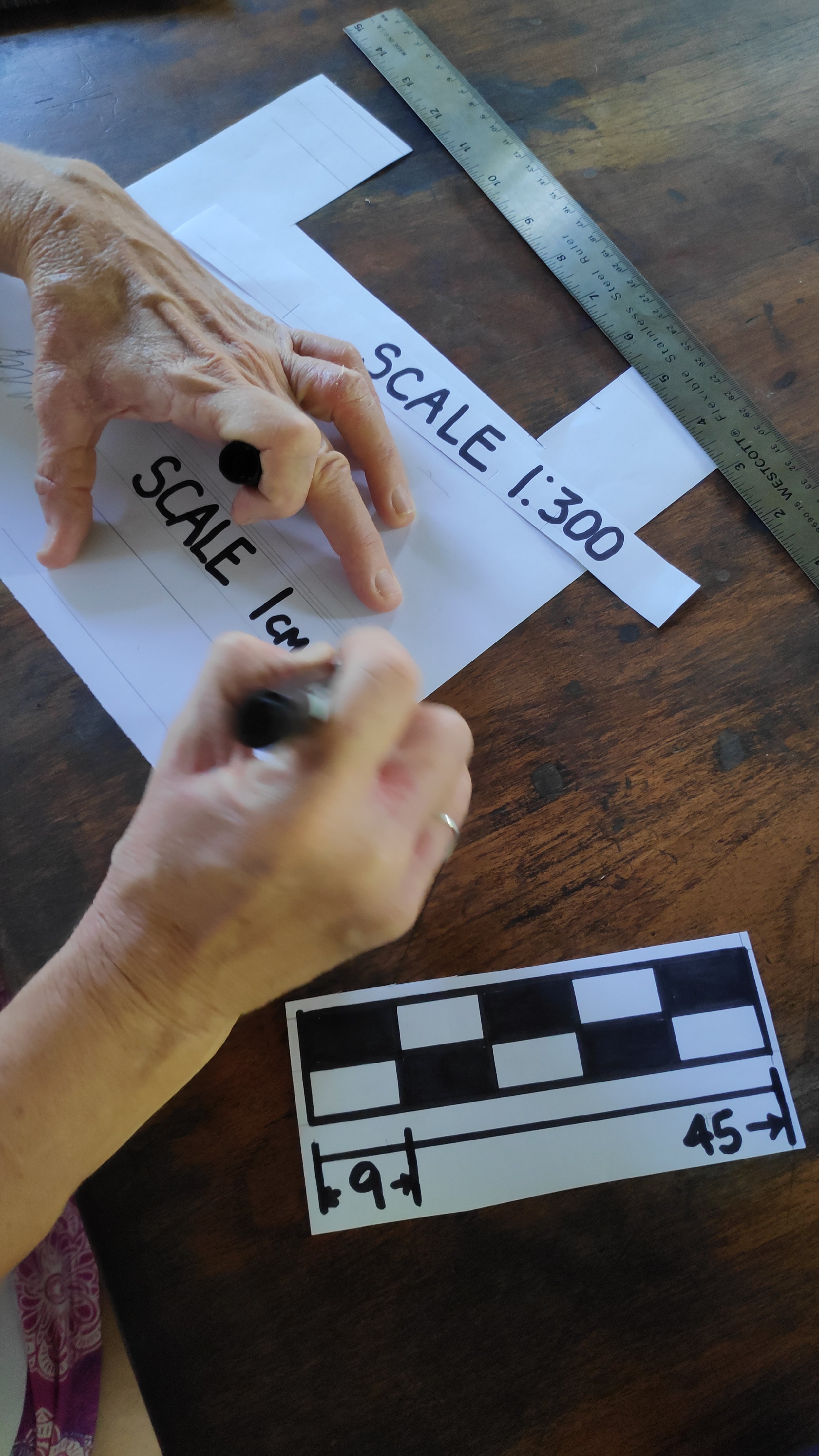

Design Tools

Different authors will have varying definitions of the principles, but most of the time the same ideas and concepts are emphasized. There are a several important methods in permaculture design that I haven’t mentioned, one of them is the sector analysis which can be defined as the analysis of different energies that usually come from outside the land and have a direct influence on it. We as designers need to decide if these should be blocked, opened-up or channeled; some of them are the sun path (sunset/sunrise, winter sun/summer sun), winds, wildlife, views, neighboring structures, roads, etc.

The sector analysis allows the correct positioning of the different elements in the space, the elements are every system in the project; from the chicken coop, to the house. These can be productive systems (agroforestry, garden beds, cheese making facility, rotational grazing system, fish pond, etc.) or infrastructures (main house, yoga deck, kitchen, guest house, etc.) One very important methodology in permaculture is the element analysis, where we asses the needs, yields and intrinsic characteristics of each and every one of our elements, that way we can decipher the possible connections between them. Always with the goal of reusing every resource to its maximum, because we know there is no waste in nature, just inputs for a new process. By realizing the interconnectivity that is possible in our project, we can move on to the creating of a web of connections, which is a matrix that connects inputs and outputs of every element. This analysis will help us chose appropriate positioning of the systems, understanding that the element with more connections should be in a central position so we can save time when managing and navigating the space. The element analysis and web of connections should be hand in hand, because even though my pigs receive food scraps from the kitchen and the main garden, they need daily care and are able to forage in the food forest, we are not going to position them too close to the house because of their known odors and sounds.

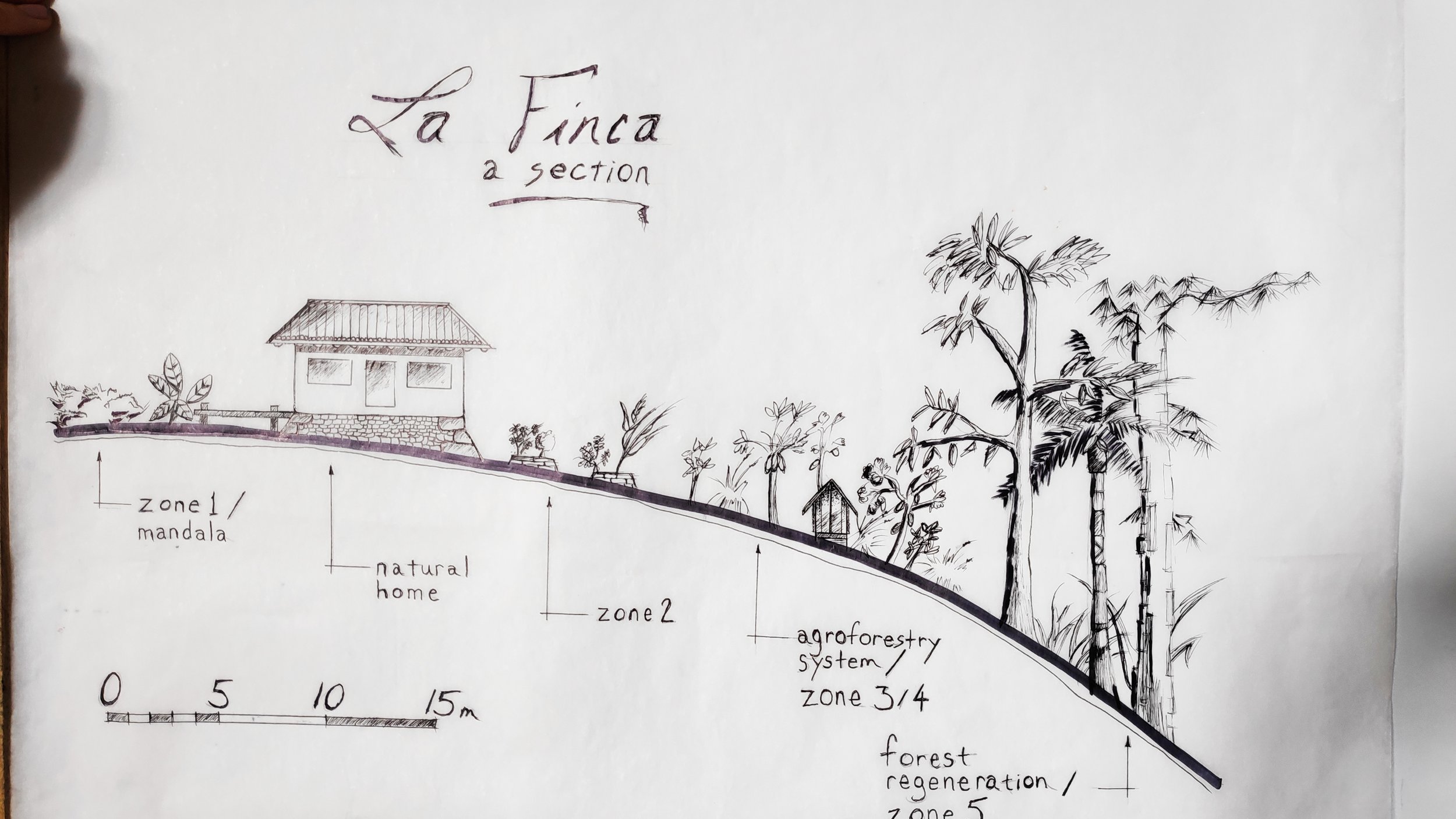

The last method in permaculture design that I’m sharing is the zone analysis, zoning is a tool to organize our project into areas that require the most and the least attention. This can be applied to a house with a small garden or to a big farm. Basically, the zones go from 0 to 5, following is a summary of what each zone may entail, remember that every project is different so the following will vary:

Zone 0: structures where permanent residents live.

Zone 1: areas that are visited several times a day, the area closest to the house and paths that are connected with important elements in the project. This zone includes a veggie garden, herb garden, greenhouse, small animals (rabbits, guinea pigs), etc. Let’s say that you have a cheese making laboratory and packing room as your main work area, if you are visiting that space several times a day, that would be part of your zone one, just like the path between your house and that facility.

Zone 2: areas that are visited at least once a day, we can have small animals and animal pens when they need to be fed on the daily, compost area, some fruit trees, more veggie beds, etc. Again, this classification will totally depend on our own daily schedule.

Zone 3: areas that are visited a few times a week. Larger food production system like a milpa, agroforestry systems, pasture lands, root crops etc.

Zone 4: areas that are visited several times a month. These are semi-wild/semi-managed areas, used for gathering materials (timber, firewood, bamboo, fiber) and can include food forests.

Zone 5: where we go to learn, where we are visitors and not managers, space that we give to nature. Many times, these are protected wildlife sanctuaries, ideally if the size allows it, 50% or more of your land should be in zone 5. In small, semi-urban and urban projects its complicated to dedicate an area to zone 5 because of the restricted space. In that case the edge of the property or even a corner where we allow native species to grow and thrive will have a big impact in the ecology of the project and the surroundings.

Concluding Thoughts

Now that we understand the basis of permaculture, its easy to find who is actually practicing permaculture. Its being practiced all over the globe in many land-based projects, intentional communities, homesteads, urban gardens. By many community leaders, innovators, architects, farmers, landscape designers, chefs, natural builders and many more.

It’s worth mentioning that permaculture can be many things, but it most definitely is not a neocolonialist tool, simply because the collective good and prosperity are keystones in actual Permaculture. As a design methodology for human habitats where some key concepts are: “share and return of surplus,” “integrate rather than segregate,” “cooperation instead of competition,” and “use and value diversity”; having an activity or development that damages local population or intends to create an exclusive bubble goes against permaculture. It’s necessary to protect permacultures name and reputation, for its reach to expand and create a better world, that is a task that we all should take seriously.

Using permaculture ethics and principles in the design of a project, regardless of its size, will promote a sustainable, low input to high output, self-reliant organism. For me permaculture is a way of thinking, a guide to understand and interact with the world, a kind reminder of our belonging to nature and a tool for living with intention. When we observe and interact with the world with permaculture lenses, we take action into choosing what is best for nature, others and ourselves, the sense of interconnection and reciprocity are in the heart of this philosophy. I believe that permaculture is a beautiful tool for positive impact and a way to create the change that we desperately need.

Learn More

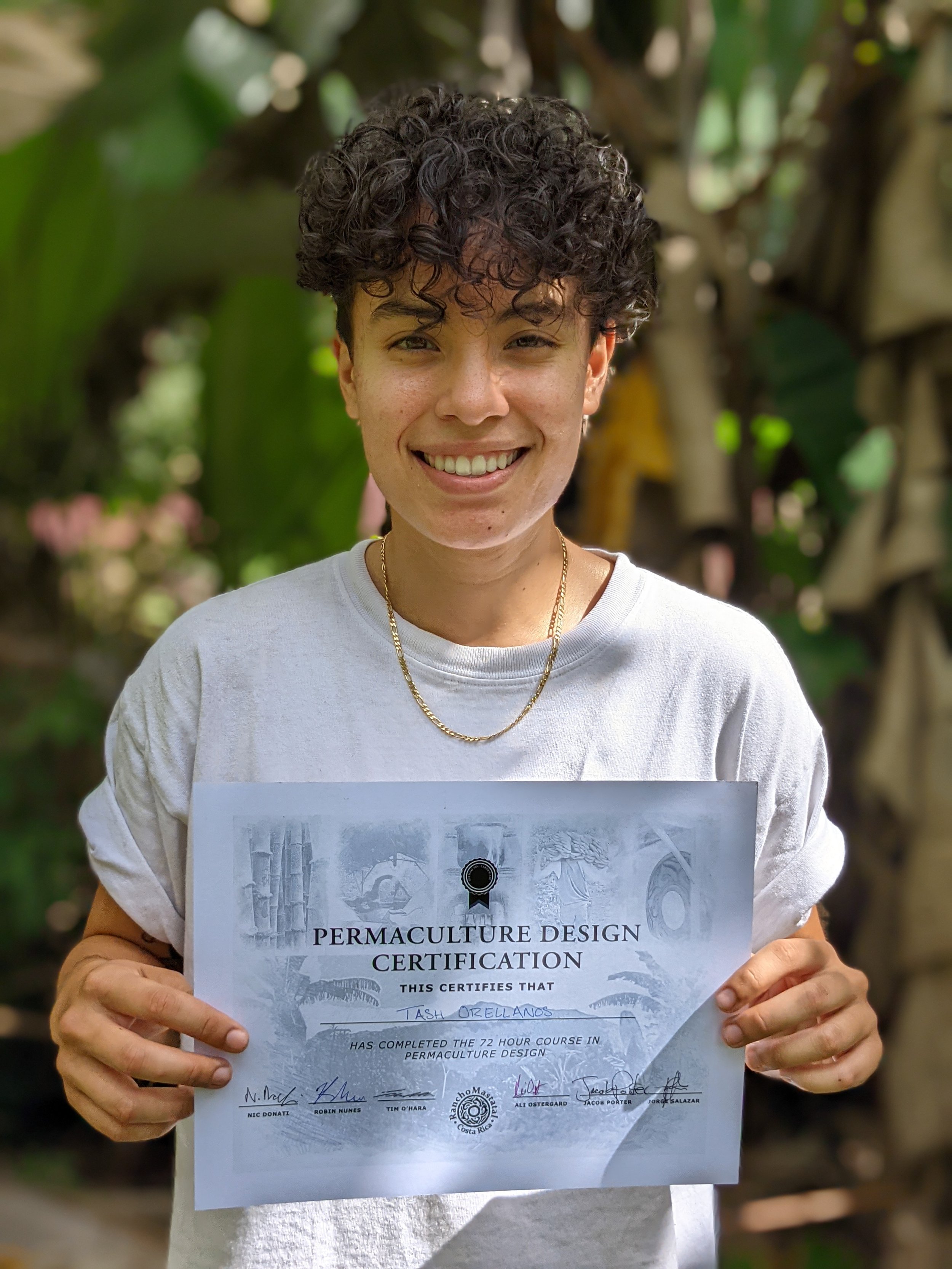

Want to learn more about permaculture design and gets hands on experience from lead experts? Join us for one of our yearly Permaculture Design Certifications or other educational workshops.

Read these past related blogs

The Problem with Permaculture: Understanding Elements and Functions

Why the World Would be a Better Place if Everyone Took a Permaculture Design Certification